jeFF0Falltrades

If you have not seen jeFF0Falltrade’s YouTube channel I recommend you give it a watch! He makes great reverse engineering content. Almost a year ago, he made a series of videos as sort of an introduction to reverse engineering and x86 assembly. Alongside the videos he made a crackme to solve as well as a Wall of Fame for people who have solved the crackme. I thought it was a fun little challenge and wanted to do a quick writeup.

The crackme

First we can check the crackme on VirusTotal just to make sure everything was legit (as is good practice). Next, lets run crackme.exe to see what we are dealing with.

Cool! It’s ASCII tic-tac-toe. You simply pick a square to place an X or O and repeat. After playing a few winning rounds and a few draw’s, we can check the binary in Detect it Easy.

Nothing interesting here. No packing and no clues as to what the binary was written with. Next, we should toss the binary into Ghidra and analyzed it using the default options. The first thing I always check are the binary’s strings. There are a lot of strings - 2781 of them. However, most are uninteresting. Strings like C:/M/mingw-w64-crt-git/src/mingw-w64/mingw-w64-crt/stdio/acrt_iob_func.c indicate this was probably compiled with GCC via MinGW on Windows. Several of the strings such as "Draw!\n\n" are noteworthy and immediately direct attention to the_main function.

First thing to note is that some symbols are here like _init_game, _print_board, and _check_game_state. So let’s just figure out how this works an walk through the functions. We can safely ignore ___main and _signal(2) since they appear to be build system or compiler added functions. So let’s look at _init_game.

Hm. Lets look at _init_board.

So here we have a loop that calls _init_square eight times. This makes sense because on the ASCII board, there are eight separated squares. We can rename local_8 to squares to help readability. Let’s see what _init_square(square * 0x25 + param_1); does each time it is called for a square.

First, to make this more readable, lets rename local_c to i and local_8 to j. We also see on line 11 0x2e or .. And on line 14 0x20 or the space character. This makes sense, the squares on the board are made of 6x6 . and space characters. The first loop iterates over each row and the second loop over each column. if ((((j == 0) || (j == 5)) || (i == 0)) || (i == 5)) is used to see if the current character is the border of the square. If it is the border, it sets the character to ., otherwise it is a space. Line 18 sets the corner of the board to a space character. So now we know that param_1 is the board array. So we can rename param_1 to board and change the type to char *. That looks much better! Now we know how the board is stored. board[i + j * 6] = '.'; shows us that the board is stored as a one dimensional array of characters. So here is what we end up with:

Now we can go back to the previous functions, following the argument that was passed to _init_square and rename/retype to for the board. Lets also change 0x25 to decimal.

board + square * 37 makes sense now, since each square is 6x6, this is the first character position in each square. Next lets go back up another level.

Here we still need to understand the first parameter here. We can see two operations are done on it. If we look at _main we can see that local_168 (the first paramter) is checked before a draw or win message is printed. If this variable is 1 the game is won, 0 for a draw, and 2 to keep the game going. We can retype param_1 to an integer but something is still off.

0x20 in ascii is the space character again. Hm. Lets create a struct. We can use Ghidra’s “Auto create structure” option on param_1. Next, we can edit the structure. We’ll name it game_struct. Next, the first field is an integer named win_state and the second field of type char and set to temp for now.

That’s much better! Now we take what we know and apply it to _main.

Lets get a few more variable figured out. iVar1 is only used on line 27 and 28. toupper() is called on game_struct.temp and the value is then printed in the victory message. So iVar1 and game_struct.temp probably stores the current player or symbol. So, we can rename game_struct.temp to game_struct.current_player and I chose to rename iVar1 to victor. We can also see another variable is used to store x or o. So lets also rename this to current_player.

Now we enter the main loop, as long as game_struct.win_state == 2. Lets look at FUN_00401c61().

This function appears to get the users input. local_14 is used to store the input from scanf(). On line 20 it also checked to make sure it is between 0 and 10. local_10 is used to store the return value from scanf(), which for one character entered should be a value of 1. There are checks for this on line 20 and it used to loop unit input is successful. iVar1 appears to be used for two things. First, it stores the return from topupper(param_2). Looking at _main, param_2 is the current_player variable. So it stores the uppercase current player for line 12 and 13, as well as 22 and 23. The variable is also used to store a character from getchar() when the function is checking for a newline. Since that isn’t important to us, I named the variable move_position. Line 21 is used to check if the square specified by move_position is an empty square. Here is what it looks like now:

Time to check out FUN_00401b6a(). We can go ahead and retype/rename the parameters since we know those.

We can again move to the next function FUN_00401aae() and change the parameters here as well. The first parameter board + input * 0x25 is again the ASCII square specified by the users input.

With the parameters solved, this function is easy to understand. It checks if a square already has a symbol in it, if not it continues and runs a function for if x or o is specified. It’s easy to guess that these two functions add the symbol to the board. But lets check.

This is cleaned up slightly, but sure enough it places X’s in the board array so that when the board is drawn, it has an X made out of X’s. With a one dimensional array for the board, the first square of the board looks like this in the memory:

1

.......x x.. xx .. xx ..x x.......x

Or with an X in square one, O in square two, and another X in square three:

1

".......x x.. xx .. xx ..x x.......x....... oo ..o o..o o.. oo .......o.......x x.. xx .. xx ..x x.......x

I renamed FUN_00401aae to add_symbols and FUN_00401b6a to add_symbols_wrapper. And with that, we can finally go back to _main and move to the next function _print_board. Again, lets go ahead and retype/rename the parameters since we know those and rename the the loop variables to be more easily readable.

This function does what it says, and prints the board row by row. It is a bit more complicated because of how the board is stored in the array, but that is all this function does. The multiple for loops are used to jump around the board array so that it can be printed row by row. At the end of each row, and after the whole board is printed, a newline is printed. Going back to _main() we move onto _check_game_state.

As per usual, let’s start by renaming/retyping the arguments. From _main() we see the first parameter is a pointer to game_struct, and the second is a pointer to the board array. We can also rename local_10 to i since it’s only used in the first for loop. Immediately thought, there is another function we need to look at: FUN_00401778(). It takes four parameters. The first parameter is board and then the rest are integers.

So, first retype param_1 to be char * and named board. uVar1 appears to just store the return value of the function. We should recognize board[square_1 * 37 + 36] from earlier. That’s the calculation it does to see if a square has been filled with a symbol or not. Line 7 checks if a square specified by param_2 is empty. If not, it checks if param_2, param_3, and param_4 are equal. If they are, it returns 1, otherwise 0. So, this function checks to see if there has been a win by a player in the squares passed to the function.

So looking back at _check_game_state, check_squares is called with i, i + 1, and i + 2 parameters for the squares. i is incremented by 3 each loop. This loops checks all three rows to see if there is a win. The next loop checks to see if there are any vertical wins. check_squares(board,0,4,8); is checking for a diagonal win, and the other call also checks for a diagonal win. The result of check_squares is used to set game_struct.win_state and game_struct.current_player. Next there is some strange logic and function FUN_00401db7. Let’s see what it does.

Hm. This function looks sus. It takes a variable as a parameter and modifies it with bitshifts and an xor. We see that it loops for 16 times over several variables. Let’s select local_18 and retype it to be char [16]. Looking back at _check_game_state, we can see it prints the variable that is passed to this function, so lets retype it to char *. And just like that we can see this most likely the flag! So lets rename param_1 to flag, rename the function to generate_flag and see how we can reach this code. Here’s generate_flag now.

Back in _check_game_state…

Let’s rename and retype local_30 to be char [16] flag. That makes a bit more sense now. Now we need to know what local_1c and local_18 are for. At line 61 local_1c is incremented each loop and used to check to see if a square is empty. If it is, it break from the loop. At line 63, it used to check if the symbol in the square is the same as the first square (board[36]). If it is, local_18 is incremented. So, to reach generate_flag we need local_18 to equal 9. So, to print the flag we would need every square to be the same symbol and there be no wins to reach generate_flag. Before we look at aproaches to getting the flag, here’s _check_game_state now:

Getting the Flag

Without debugging

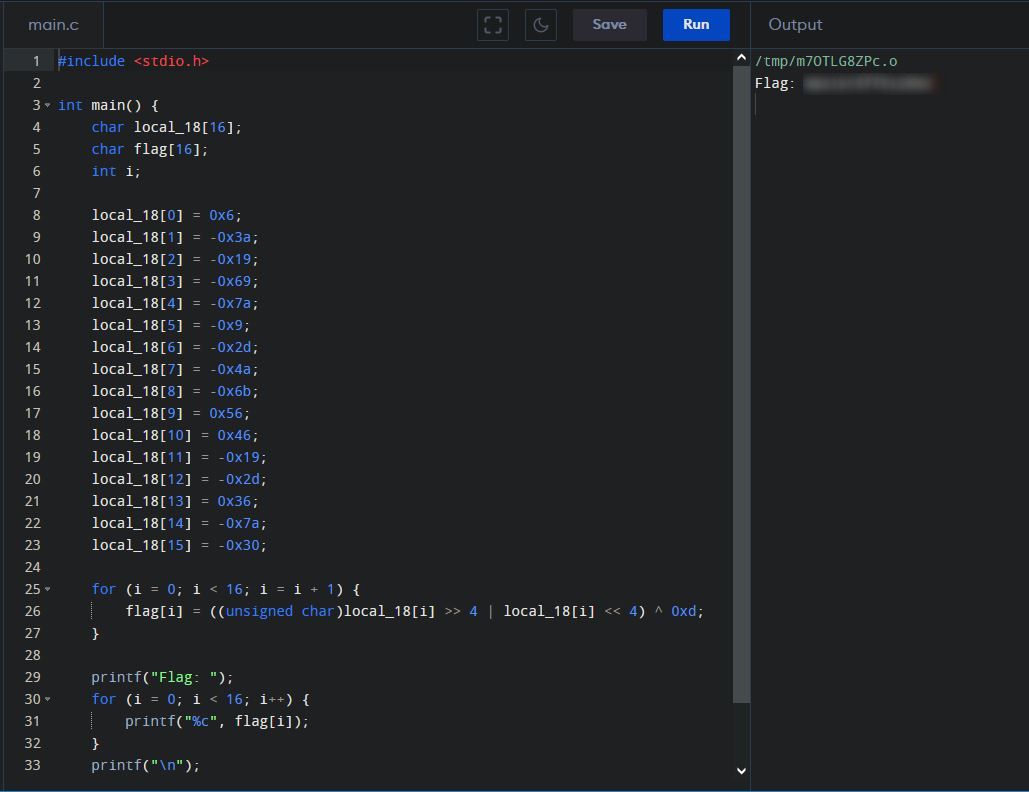

C

Since we have the encoded flag, we can almost directly copy and paste the code from Ghidra, add a header file, and print the flag, like so:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

char local_18[16];

char flag[16];

int i;

local_18[0] = 0x6;

local_18[1] = -0x3a;

local_18[2] = -0x19;

local_18[3] = -0x69;

local_18[4] = -0x7a;

local_18[5] = -0x9;

local_18[6] = -0x2d;

local_18[7] = -0x4a;

local_18[8] = -0x6b;

local_18[9] = 0x56;

local_18[10] = 0x46;

local_18[11] = -0x19;

local_18[12] = -0x2d;

local_18[13] = 0x36;

local_18[14] = -0x7a;

local_18[15] = -0x30;

for (i = 0; i < 16; i = i + 1) {

flag[i] = ((unsigned char)local_18[i] >> 4 | local_18[i] << 4) ^ 0xd;

}

printf("Flag: ");

for (i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

printf("%c", flag[i]);

}

printf("\n");

return 0;

}

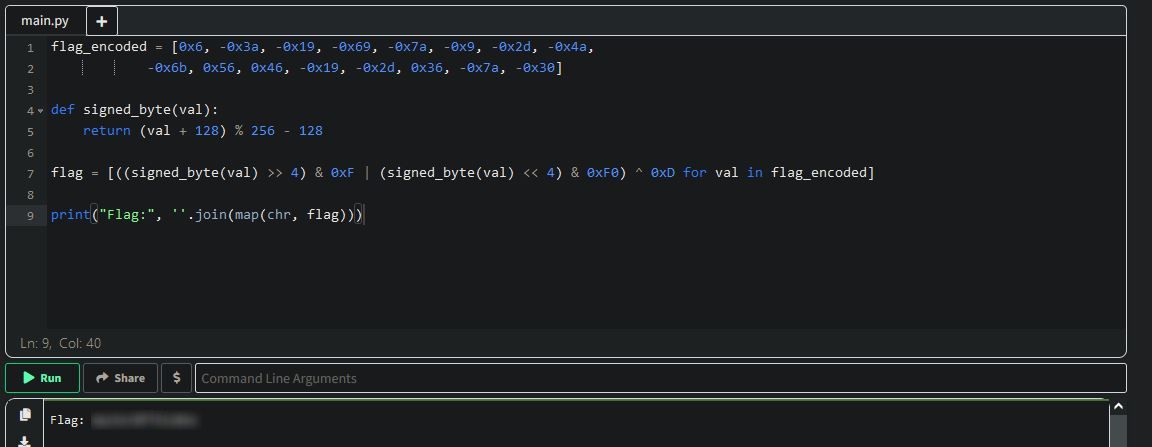

Python

We could also recreate the logic in Python:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

flag_encoded = [0x6, -0x3a, -0x19, -0x69, -0x7a, -0x9, -0x2d, -0x4a,

-0x6b, 0x56, 0x46, -0x19, -0x2d, 0x36, -0x7a, -0x30]

def signed_byte(val):

return (val + 128) % 256 - 128

flag = [((signed_byte(val) >> 4) & 0xF | (signed_byte(val) << 4) & 0xF0) ^ 0xD for val in flag_encoded]

print("Flag:", ''.join(map(chr, flag)))

Debugging

Jump to the function

In IDA Free, we can easily find the function that generates the code. We attach using the debugger and then we can set a breakpoint just after the checks for a win. This is close to where the code calls the flag generation function so there is less that can go wrong. Next, select a move and the breakpoint will be hit. Then we can set the instruction pointer to the block of code that calls the flag generation function.

And then resume the program.

Success!

Only ZF?

But, what about without setting the instruction pointer or explicit patching? It is possible to reach the code by only modifying the zero flag at a few points. Here are the breakpoints for that:

This post is long enough as is, so I won’t explain exactly how it needs to flow. There is more than enough explained in the post for the reader to figure that out. In summary, always use one character, avoid the 4 checks for a win, and you do have to leave the input function. Best of luck!